How We Integrated ElasticSearch and Rails at Pose

Elasticsearch is a tricky integration point for many Rails apps. When we added search to Pose we went through a months long process of refinement, trying out different solutions and ultimately rejecting them and building our own as shortcomings became apparent and complexity rose. In the end we wound up building our own client, Stretcher, and our own set of Rails integration tools which are not yet open-sourced, but are described in this document.

Overview

Our Pipeline

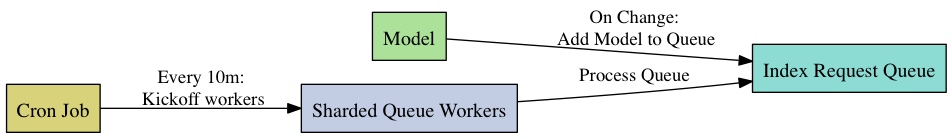

Our first major concern was implementing a pipeline for converting our model objects to elastic search documents. We wound up implementing an indexing strategy that boils down to:

For initial imports of tables this would obviously not work as we’d need to create a queue entry of multi-million row tables. For that we have a bulk_worker job that will index every record in a table, going through the table in chunks.

Both the index_requests queue worker and the bulk worker are implemented as DelayedJob jobs capable of running in a parallel, sharded fashion.

A Sample Search

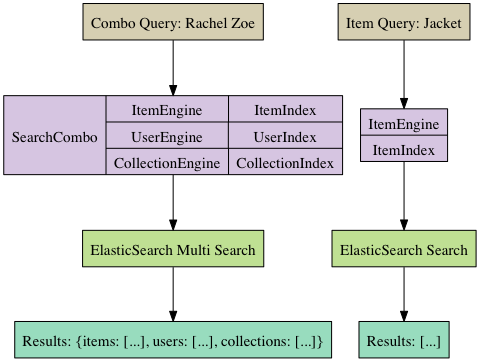

We support two main types of search API, searching a single index, and searching across multiple indexes. These map to the standard ElasticSearch “_search” endpoint, and the MultiSearch “_msearch”, endpoints respectively. Both types are illustrated in the diagram below. Note that searches are a coupling of an Engine with an Index. In our class structure an Engine is a class used for building a query, while an Index represents a specific ElasticSearch Index.

For those coming from a SQL background, the notion of mapping a query to different indexes may seem strange. However, in ElasticSearch it may be the case that maintaining two different indexes of the same data makes sense. We’ve found supporting multiple indexes invaluable in terms of A/B testing different rules regarding what gets indexed, what gets boosted, and how it gets analyzed. Additionally, from an operational perspective we can bring a new index online in the background, then seamlessly switch over.

Why We Don’t Index in Real-time

Luckily real-time indexing was not a business requirement for us. While trial to implement real-time indexing brings a lot of fragility and potential for failure. The easiest way to use ElasticSearch is to simply add an indexing PUT request to ElasticSearch straight into model hooks, we eschewed that for several reasons:

- Indexing bound to the HTTP request response cycle impacts response times to users.

- Indexing can be slow and expensive. Some of our objects require serializing multiple associated models each time indexed.

- Frequently updated models would wind up being indexed multiple times per second. On Pose a ‘love’ action, which can have high velocity, requires a re-indexing. By using a queue we can ensure it only gets re-indexed once per 10 minutes at most.

- Breaking indexing out to a background task gives us better a better failure mode given a downed search server.

- Bursts of traffic are smoothed through the queue.

- Periodic indexing lets us use ElasticSearch’s more efficient bulk indexing api.

- Results are cached by our Rails app in memcached anyway to keep load on ElasticSearch low, negating the value of real-time.

Efficiency Concerns

One thing we discovered quickly is that indexing data should be fast, and must be parallel at any reasonable sort of scale. That requirement permeated every decision we made on the indexing side of our implementation.

Why we kept all the work in Postgres

While an RDBS is not a queue, it has sufficient queue-like attributes for our needs. By being careful to use queries that scaled well–in our case a combination of modulo and range queries (described later in this section)–with even large queue sizes we are able to meet our performance requirements while keeping our infrastructure simple.

Additionally, the choice of PostgreSQL meant that queue actions would be hooked into transactions around our models. This ensures that failures in the object creation life-cycle do not result in queue entries.

Efficiently Queueing Index Requests

Special care was taken to write SQL queries that would allow for efficient indexing of ElasticSearch data. Firstly, the queue for index requests is implemented as a table ‘index_requests’ in our PostgreSQL database. Using a database table for this queue is fast enough and has the added bonus of being transactional.

Inserts to this table first check for a previous IndexRequest row for the specific object being indexed. This query would optimally be an ‘upsert’, but since such operations in Rails are a bit tricky without writing complex bare SQL we opted to simply perform a ‘SELECT’ for duplicate records before writing to the queue. While this is a race, the worst case outcome of this is indexing items with a high change rate once or twice more, a tolerable tradeoff.

Efficiently Reading Off The Queue

The query to read off the queue simply grabs items in an un-ordered fashion using a modulus operation for sharding between workers. In PostgreSQL querying using a ‘WHERE id % x == y’ is an efficient query in most cases so long as an ORDER BY clause is omited. While this means we do not read off the queue in order our business requirements do not require speedy propagation of changes to the index.

Efficiently Indexing a Large Un-indexed Model

Indexing a whole table that has never before been indexed was implemented apart from the queue. We opted to traverse the table in integer ranges over our primary key for fast and even performance iterating over the table. Paging with libraries like kaminari or will_paginate gets slow with high page numbers (around page 100,000 for instance) as the DB has to get a total order for the table.

Instead of using paging libraries the sharded workers find the max id at the start of indexing, and go through it in integer ranges, with queries like ‘id >= 100 AND id <= 199’. These workers are sharded, using a modulo for page ranges. Newer records than the MAX id found at the start of the bulk job will be picked up by the index request queue.

Our Class Structure in Depth

The Foundation

ElasticSearch and an SQL server have very little in common, following this our supporting class structure for ElasticSearch looks very little like ActiveRecord. API access to ElasticSearch is performed through the Stretcher ElasticSearch client we wrote. The classes we went with are as follows:

- Index: Maps to an ElasticSearch index, includes the Stretcher client and performs IO

- Engine: Maps to an ElasticSearch query

- Combo: Maps to an combination of queries / indexes using the multi search api

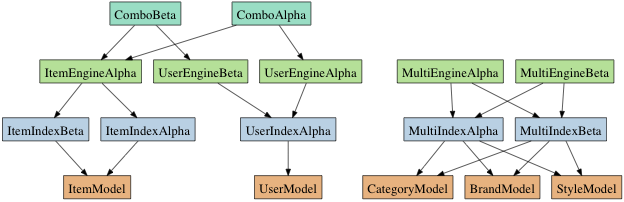

A diagram of this structure showing some of the possible combinations of these classes is shown below:

One of the attributes of this architecture that may seem strange and un-ruby/rails like is using a full class for a query. ActiveRecord, for instance, uses class and instance methods on a model for queries/scopes. Our rationale behind our Engine query class was that ElasticSearch queries can be very complex, and have a large amount of supporting code involved in their generation. Encapsulating this logic as methods alone would have lead to bloated and confusing classes.

It should be noted the index classes implement a ‘client’ method that is an instance of Stretcher::Index, through which all actual elastic search operations are performed.

Multiple Indexes Per Model and Multiple Models Per Index

One of our main criteria in building out our architecture was supporting multiple indexes per model. This was important because:

- ElasticSearch indexes are not 1:1 mappings of your Rails models, they may have different tokenization, boosts, and even entirely different fields.

- Multiple indexes ease operational concerns, letting you deploy a new index in parallel to an existing one, letting us populate it before switching to it.

- When it comes to experimental features we’ve found supporting multiple indexes per model to be quite useful. We can run a sandboxed experiment and watch it react to live data in isolation.

We also wanted to make sure that we could cleanly map an index to multiple models. ElasticSearch supports multiple document types coexisting within a single index, something we exploit for our upcoming autocomplete feature. Each Index class in our class structure has a list of “indexable_classes” that it can index.

The Index Registry

One class we’ve ommitted from the previous diagrams is our IndexRegistry class. Our Index classes must be instantiated with a Stretcher::Search instance to provide connectivity, and a prefix parameter for namespacing–important when sharing a single ElasticSearch server between multiple staging environments. Additionally, the IndexRegistry provides lookups for Index objects based on model classes, letting us figure out which Index instances need to be updated when a given ActiveRecord model is updated.

Why We Wrote Our Own ElasticSearch Client

There were a number of available ElasticSearch clients when we started our project. We tried some of the more popular options, but after a couple months it was apparent they were not up to the task. We wound up writing our own client, Stretcher for the following reasons:

- Bad APIs: The clients we vetted mapped to ElasticSearch in inconsistent or confusing ways. ElasticSearch’s API is complex and does not have very complete docs. A bad API means reconciling already unclear docs through an unnecessary abstraction layer, a constant source of frustration.

- Inefficient Rails integration: We wound up writing our own high performance classes for importing data as described earlier, Tire in particular recommends will_paginate, which is extremely inefficient for traversing large datasets. Fast importing is not hard, but is not trivial either.

- Poor support for multiple indexes per Rails model: This was important for us, our

Indexclasses hook into models, not the other way around, keeping our classes small and flexible. - Incomplete APIs: Stretcher does not attempt to describe the ElasticSearch API with complex objects, but is mostly a DSL for building URLs and request bodies, then returning JSON as hashes. This let us implement our client quickly.

- Inefficient connection handling: Stretcher uses Net::HTTP::Persistent to efficiently re-use a single keep-alive connection in a thread-safe manner.

Only the Start

We haven’t been using ElasticSearch for very long, perhaps only 6 months. Hopefully this information will be useful for others in the Rails world! I’ll be following up with new information as we go further with ElasticSearch!